With Valentine’s Day over, ShoreBread has gone back to focusing on February as Black History Month. In that vein, we decided to do some historical digging by tracing the story of another great abolitionist from the Shore, Harriet Tubman.

Tubman was born into slavery as Araminta Harriet Ross around the year 1820 on a plantation outside of Cambridge, Maryland. Like Frederick Douglass, she never knew her exact birth date or year. Her mother and father were both slaves who were brought to the same plantation once their two masters were married. Tubman was part of a large family and was one of nine children born to her parents.

Growing up in slavery, Tubman faced especially difficult events throughout her adolescence. When Tubman was just a young girl, three of her sisters were separated from the family when they were sold to distant plantations. Tubman also experienced multiple accounts of physical abuse before she reached adulthood. According to historians, one time while at the market, Tubman refused to help an overseer punish another slave, leading the man to hit Tubman in the head with a two pound weight, causing permanent mental damage. As a likely result, Tubman continually suffered seizures, headaches and narcoleptic episodes for the rest of her life.

In 1844, Tubman married a free black man named John Tubman. It was during this time that she changed her first name to Harriet, most likely in honor of her mother. Five years later when Tubman’s master died, she successfully escaped with her two brothers to Philadelphia. As a reward for their capture, a local newspaper advertised a $300 compensation. Her brothers started to doubt their safety while in Pennsylvania and decided to return to Maryland while Tubman remained up north.

In 1850 however, Tubman learned that her niece Kessiah and her two children were being sold at auction and would most likely be moved somewhere far away. Luckily, Kessiah’s husband won the bid for his wife and children but the family still feared for their safety. To insure their protection, Tubman helped to move the entire family to freedom in Philadelphia.

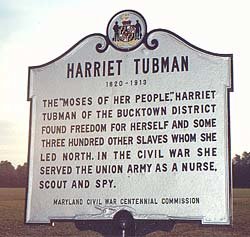

Soon, Tubman was moving her parents, siblings and other slaves through the Underground Railroad to freedom above the Mason-Dixon Line. She became very efficient at helping people escape slavery, guiding over 90 people north and earning the nickname Moses along the way. In 1850 the Fugitive Slave Act was passed which made it legal for slave owners to reclaim escaped slaves if they were found up north. This piece of legislation did not discourage Tubman but instead spurred her to extend the Underground Railroad to Canada, where slavery was illegal. Tubman was once quoted saying “I was the conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can’t say; I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.”

As a conductor, she also met other abolitionists on her dangerous journeys. In 1851, Tubman made a stop to hide escapees in the home of Frederick Douglass. Later in her career, she met John Brown, another abolitionist who spent time in Maryland. John Brown believed that the only way to end slavery was through violence. He led many bloody uprisings throughout America, ultimately becoming truly infamous in his raid on Harper’s Ferry. This uprising in particular brought the two abolitionists together when Brown asked Tubman to help with the recruitment of troops.

During the Civil War, Tubman worked for the Union as a cook and nurse and later as a scout and spy. She also became the first woman to lead an armed expedition in the war when she guided the Combahee River Raid, which liberated more than 700 slaves.

In 1859, the abolitionist Senator William H. Seward gave Tubman a piece of land outside Auburn, N.Y. where she and her family lived. Ten years later, she married a Civil War Veteran named Nelson Davis, and later the two adopted a girl named Gertie. Tubman also had a biography written about her entitled Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman, written by Sarah H. Bradford.

Tubman had surgery on her head in 1913 to help fix the brain trauma and complications that she had experienced her whole life. She retired to The Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged which had opened in 1908 in her honor. However, later that year she died of pneumonia and was buried with military honors.

Tubman continues to be a prominent figure in American history. After her death, she was the third most famous American who lived before the Civil War, trailing only behind Betsy Ross and Paul Revere. Today there are many memorials set in place to honor her hard work and bravery including the Harriet Tubman Museum in Dorchester County, several sites in New York, a highway dedicated in her name and a statue at Salisbury University.