The crew hurried to board, they were due in Washington DC to pick up President Benjamin Harrison and the Secretary of the Navy, Benjamin Tracy—they were departing from Brooklyn. Also boarding were collie dogs and a Maltese cat, pets of the sailors.

Their vessel was the Presidential yacht, the Despatch. She was the high point of luxury built initially for a private owner in 1873 at a cost of $200,000. This wooden schooner rigged steamship had played host to world dignitaries, and was the official vessel of five presidents—undoubtedly one of the most notable ships of the time.

Just prior to leaving the harbor, a black cat jumped on board. Sailors are notoriously superstitious, and this group was no exception. Black cats are considered a bad omen, and the crew searched the vessel for this cat, hoping to toss it off the ship. Their efforts were futile—they had to set sail with the unlucky cat on board.

On October 10th, 1891 off the coast of the Virginia, the darkness was blinding. Waves were crashing all around, splashing over the side. The weather was thick and murky. The Lieutenant commanding the Despatch saw a light up ahead—the only beacon in an otherwise black night. He steered towards it, thinking it was the lighthouse ship, a marker for all ships coming close to the then treacherous coast of Assateague Island. Instead he ran aground, sealing the fate of the Despatch. The light wasn’t the lighthouse ship normally situated out in the ocean–unknown to the crew it had been moved to undergo repairs–it was the actual lighthouse, whose beam drew the Despatch aground.

After the wreck, the Lieutenant said he had never witnessed such treacherous surf. Despite the conditions, all 79 sailors on the Despatch and their pets were rescued by the crew of the Assateague Life-Saving Station. After every living thing had been rescued, the sailors watching the wreck from the shoreline observed the black cat—the unlucky stowaway hidden the entire voyage, climbing high about the rigging. The next morning, amongst the cigar boxes, cans of ham, furniture, wood from the ship itself, and other remnants, lay the dead body of the black cat, credited by many of the crew as being the unnatural force that brought down the Despatch.

The Ocean City Life-Saving Station Museum is dedicated to remembering stories of wrecks such as the Despatch, and countless others coming from the nineteen Life -Saving Stations that used to dot the coasts of Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia. In all over 300 ships were total losses, but the dedicated crews of the Life-Saving Stations (after 1915, they would come to be known as the U.S. Coast Guard) had a remarkably high rate of successful saves, especially considering the time period and equipment available.

But not all stories had happy endings, lives were certainly lost. The museum is a time capsule devoted to both triumph and tragedy in the waters off our coasts. Often the rescue attempts occurred in terrible snowstorms, with snowdrifts as high as a man’s head, when the beach all but disappeared beneath the pounding waves.

As with any place that holds history, the Ocean City Life Saving Station Museum may also house a few spirits of those who endured these stories first-hand. Museum Curator Sandy Hurley recalls hearing from visitors who are more in-tune with the realm of let’s say, the “spirit world.”

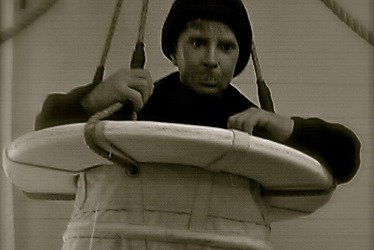

“We’ve had people who have visited say they feel the presence of a little girl. And in the life-cart, which came from a station in North Carolina and saw a lot of action in terms of shipwrecks, people have looked inside and said they saw a spirit of a man drenched [after rescue] shivering.”

As the area gears up for Halloween, consider visiting the Ocean City Life-Saving Station Museum. It houses not just the stories of the Life-Saving Stations, but also a great deal of Ocean City history. The voice of “Laughing Sal,” the former boardwalk staple can still be heard echoing through the halls—her laughter alone the perfect eerie sound bite. The museum celebrates all local history, some of which may be a little bit…haunted.