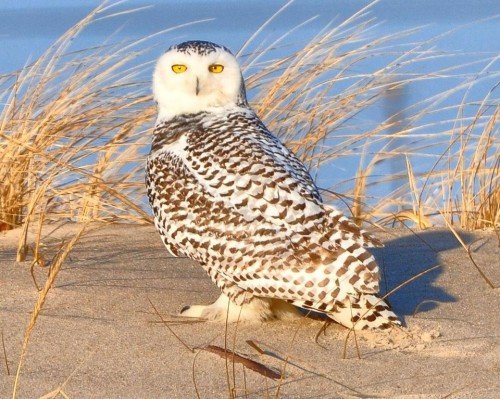

By now you’ve most likely seen the amazing photos of snowy owls spotted in our area. If not, then perhaps you remember Hedwig, the snowy owl made famous by the Harry Potter series. If you’re still in the dark, you’re in luck, because we’ve gathered a wealth of information on the beautiful birds that have shown a spike in population in our area as of late…a surge so significant that we might not have the chance to see one again in our lifetimes.

After hearing rumors of the birds’ prevalence at Assateauge and along Delaware’s seashores, we decided to do a little digging of our own, consulting Maryland Coastal Bays Program Education Coordinator Carrie Samis for a discussion on the snowy owl irruption, where to spot one, and to learn more about Project SNOWstorm.

“It’s probably the biggest irruption that we will see in our lifetimes,” said Samis this week, pointing out that this is the largest snowy owl irruption that we’ve seen in at least 40 years. So what exactly is an ‘irruption’? Snowy owls have been known to head south in unpredictable invasions known as irruptions. While the irruptions are generally related to food or babies, there is much that is still unknown about the irruption phenomenon – or why we are currently experiencing the biggest irruption in decades.

Samis was quick to debunk one popular myth circulating that suggests that snowy owls have moved south due to a lack of food or because they are starving. In fact, this couldn’t be further from the truth. According to Samis, “this was a hugely successful reproductive year for snowy owls in the arctic because the food was so plentiful.” What’s more, the snowy owls are perfectly healthy during irruption years, and they would need to be to do so much traveling.

The increase in sightings was first noticed around Thanksgiving. Since then, snowy owls have been popping up all over the country, from as far north as New England, to as far south as Florida. The snowy owls have even been spotted westward, said Samis, explaining that “Chicago and Cleveland have a huge number of birds right now…so there are birds everywhere.”

With the once in a lifetime chance at their fingertips scientists quickly began organizing efforts to track the irruption and learn from it. Unfortunately, the unanticipated nature of opportunity meant no budgets or funding was in place. An Indiegogo site was quickly launched in an effort to raise money for Project SNOWstorm – a collaborative research effort to learn more about this historic snowy owl irruption. In just 12 days, over $19,000 was raised. With the original monetary goal set at $20,000, the project is well on its way to being fully funded, but Samis explained that “if they reach that goal they are going to continue to raise funds.” Currently the $20,000 goal has been slated for purchasing and implementing 20 to 25 transmitters to track snowy owls. Any additional funds could be used for future research.

So far two snowy owls have been successfully transmitted, the first right here at Assateague. The cutting-edge tracking technology will follow the movements of snowy owls in astounding detail, and potentially for years at a time. The solar powered transmitters record locations in three dimensions (latitude, longitude and altitude) at programmable intervals as short as every 30 seconds. The result is unparalleled details on the movements of snowy owls, 24 hours a day. “It’s a tremendous opportunity to gather a lot of data that we haven’t been able to get before,” said Samis.

“The Assateague bird has flown well over 250 miles so far,” said Samis, explaining that so far the transmitter has shown the owl’s flight path from Assateague to the Delaware seashore to New Jersey. Conversely, the second owl (tagged in Wisconsin) has only traveled within a one to two mile radius so far. The third owl was fitted for a transmitter just the week at the Philadelphia Airport.

Another exciting aspect of the irruption has been the public interest, most notably within the social network sphere. “This is all occurring when social media is huge so information is getting out really, really quickly,” said Samis. “There’s this merger of science and pop culture and social media right now and people are excited and there are ways for people to be involved.”

There are a number of ways people can get involved starting with the Project SNOWstorm website, Indiegogo page and Facebook page. You can also follow a map of the ‘Assateague’ owl’s movement here. Additionally, both Maryland and Delaware Birding Groups have social media sites for reporting your own findings, as does eBird.org.

As for where to go for your own snowy owl sighting, Samis pointed out that “they like big open areas that are similar to their habitat,” such as the coastlines, farm fields, or airports. However, as is the case with any wildlife sighting, always practice caution and courtesy. “Keeping a safe distance is really important,” said Samis. “You want to be respectful of the bird and not changing their behaviors in any way.”

For more information on the snowy owls and Project SNOWstorm, the Ward Museum in Salisbury will be hosting a panel discussion of the snowy owl irruption Wednesday, January 29 from 4pm to 6pm. The panel will include Samis, as well as veterinarian Cindy P. Driscoll and ecologist David F. Brinker. No registration is required, with a suggested donation of $5. For more information on the event, contact the Ward Museum at wardeducation@salisbury.edu. We hope to see you all there!