The Eastern Shore is much more than just it’s well-known resort areas, it’s an immense landscape steeped in history, home to a number of prominent leaders who helped usher in vast societal changes. In honor of Black History Month, Shorebread is pleased to feature two titans of history, born right here on the Eastern Shore. Consider taking a day to step back in time, and visit the sites on the shore that once played pivotal roles in history.

Harriet Tubman, previously featured in this Shorebread article, was the “conductor” of the Underground Railroad—a secret network used to bring escaped slaves to the safety of the north. The Harriet Tubman Museum in Dorchester County—about to hold it’s annual banquet honoring Tubman on March 10th—honors the life of this brave sister of the shore. The Finding A Way to Freedom Trail, allow visitors to trace Tubman’s steps, mapping out the importance of the Eastern Shore in the Underground Railroad.

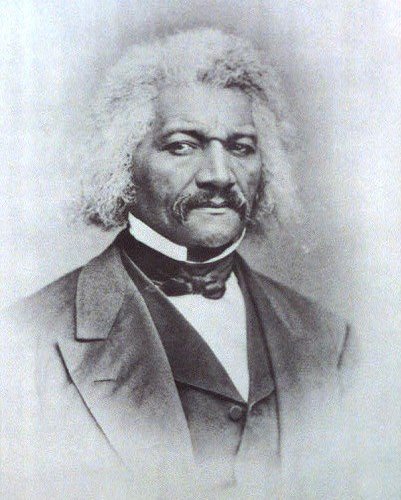

Frederick Douglass, (born as Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey), the famous abolitionist and orator, was also an Eastern Shore native; although there isn’t a museum devoted to his life, here—the renown that would eventually come to Douglass, occurred from his work and involvement in government that occurred elsewhere. The time Douglass spent on the Eastern Shore, born into slavery, served as the fuel igniting his passion and courage to bring the plight of millions of slaves to light, playing an instrumental role in the abolition of slavery.

|

According to his own autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, a Slave, Douglass says he was born, “in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton in Talbot County, Maryland.” The year of his birth, 1817 or 1818 is an approximation, as is the location described. The plantation of his birth was called, Holme Hill Farm—and is where he spent the early years of his life. Douglass was separated from his mother at an early age, and was raised by his grandmother. When he was about six years old, he was ordered to Wye House Plantation. Here he encountered his first real glimpses into the harsh realities of slavery. He also met Lucretia Anthony Auld, who wished to protect the young boy. She arranged for him to travel to Baltimore, which is where he first learned to read. As was custom at the time, Douglass was considered property, and when the patriarch of the family who retained ownership, Aaron Anthony died, Douglass was passed back and forth between the Eastern Shore and the ship building area of Baltimore, Fells Point, as the family assets were divided. Eventually, Douglass came to live with Captain Thomas Auld, and his wife on Talbot Street in St. Michaels. He was caught teaching Sunday school to slave men, and the neighbors threatened to shoot him. Douglass was then sent to a “slave breaker” named Covey. He famously got into a two-hour scuffle with Covey, which resulted in a draw, or Douglass winning—depending upon the version. But the outcome was the same—Covey left him alone. |

|

|

Douglass later planned an escape with five other men. Their plans were found out, and the men were brought to jail and dragged behind horses from St. Michaels to Easton. Eventually, Douglass’s bail was paid by Thomas Auld. Douglass was sent to Baltimore once more to work in the shipyards, and from there he eventually escaped to freedom. Douglass became a famous orator, author, played an instrumental role in the abolition of slavery, and even enjoyed life as a politician, serving as the U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia, a first for an African American. He was undoubtedly a pioneer of his time, and his work paved the way for Civil Rights in the United States. According to the Historical Society of Talbot County, Douglass never lost his fondness for the Eastern Shore. He would return four times. On one trip he came back to make peace with Captain Auld in St. Michaels. During another, in 1878 he was a guest of the Talbot County Republican Party, speaking to crowds at two churches and to a mixed group at the Court House. During this trip he also attempted to look for his birthplace, but the cabin no longer existed. In 1881 he returned to Wye house, and was given a glass of wine in the house. An 1893 trip was reportedly to scout retirement homes on the shore. Douglass died in 1895. |

|

There is a plaque erected near the site of Douglass’s birth by the Tuckahoe River in Talbot, County. It’s located just a few paces away from the bridge over the Tuckahoe River, dedicated in his name. The exact geographical location can be found, here. Additionally on the shore, the Naab Research Center at Salisbury University also houses information on the life of Frederick Douglass as part of its Special Exhibits and Collections. The St. Michaels Museum at St. Mary’s Square may offer the most tangible evidence; it houses displays showing the properties where Douglass lived or worked during his time in St. Michaels—many are still standing today. The muesum re-opens for the season in May 2012. Elsewhere, the Banneker-Douglass Museum in Annapolis pays tribute to the life of Frederick Douglass, as does the Frederick Douglass Museum and Caring Hall of Fame, located in Douglass’s first house in Washington, D.C. |

|

*Photos from The Historical Society of Talbot County and The Historical Marker Database.